UK details Kentucky’s role in runaway slave trade

Published 4:10 pm Monday, July 10, 2023

BY JACALYN CARFAGNO

Kentucky Lantern

Throughout the late spring of this year a group of nine University of Kentucky students did work that no one had ever done before.

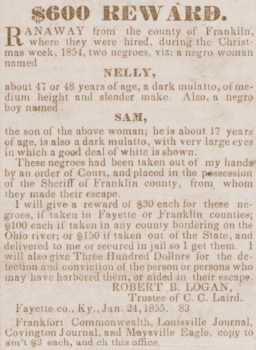

They scrolled through digital copies of early Kentucky newspapers, looking for advertisements seeking the return of people who had fled slavery, to record and preserve them.

“Ran away last spring, a man named Bartlett,” began one of the ads found in the Kentucky Gazette in 1803. “Uncommonly stout and broad across the shoulders, very dark complexion, his eyes sunk deep into his head, when spoken to generally puts on a smile but other times he has a thoughtful, ill look and possessing a great share of cunning acquiescence.”

Once owned by Colonel William Montgomery in Lincoln County, the ad said, he was sold to Henry Hall of Shelby County in 1801. The slaveholder trying to get him back lived in Natchez, Mississippi, and thought Bartlett might be trying to make his way “to Kentucky to his former place of residence.”

The reward for returning this stout, cunning man was $100, close to $3,000 today.

Although the description of Bartlett is exceptionally detailed and the amount offered for his return is unusually large, advertising for the return of human property in early Kentucky was very ordinary.

“Each ad is probably the only record that exists for a whole person’s life,” said Caden Pearson, a history major, who recorded the ad for Bartlett.

In a matter of weeks the students found more than 700 ads that ranged from the vivid and specific like that for Bartlett to descriptions so generic it “almost makes you wonder if they even cared if they got the same person back,” Pearson said.

These ads, and thousands more that University of Kentucky research librarians and historians believe remain to be found in historic Kentucky newspapers will join the national digital archive Freedom on the Move.

Based at Cornell University, Freedom on the Move’s goal is to create a database containing every runaway slave ad published in the United States from the Colonial Period until slavery was abolished in 1865 by the 13th Amendment.

“It’s heartbreaking but it’s also inspiring,” said Vanessa Holden, the history professor at UK who formed the link with the national archive.

The descriptions often include scars from beatings, missing limbs, fingers and toes as well as evidence of sexual violence. “There are a lot of ads for young girls, 13, 14,” Holden said. “They’re described as beautiful, their hair is described, their stature is described, they’re described as attractive. And then you look to see who the enslaver is and it’s a guy who is significantly older.”

But, horrible as it all is, she’s inspired by the fact that they left, even if they knew they would likely be recaptured. “It’s really empowering to learn stories of resistance. It’s really important to know that people fought back,” Holden said. “Can you imagine,” she said, in 1803 striking out alone as a runaway slave into the Kentucky wilderness? “We’re talking about people who are making these courageous leaps.”

Holden, an associate professor of history and African American and Africana studies and director of the Central Kentucky Slave Initiative, joined UK in 2017.

That year she also became part of the group that was working to make the idea of a digital registry into the reality it has become. By lucky coincidence, she arrived in Kentucky just as the project was getting underway and at UK, which has the biggest collection of historic newspapers in the state.

“Kentucky and Kentuckians are everywhere,” in the ads, Holden said. “Thanks very much to the slaving industry right here in Lexington, black Kentuckians are sold all over the American South,” she said. One of many misapprehensions the archive destroys is that enslaved people were only running to freedom. As was the case for Bartlett, “people looking for them often thought they might be heading back to Kentucky to be near family,” Holden said.

Not all the ads are placed by slave owners, there are also many from jailers — a very loose term that could include an actual public official but in many cases also meant just any white person who had a place to tie up people, often called slave jails or holding pens.

Sometimes the people were being held while a slave trader accumulated enough people to make up a coffle to take South, sometimes it was a person who had run away and the ad hoc jailer was looking for a reward from the owner. If they weren’t claimed within a certain time the jailer could sell the person and keep the money.

“It’s really crass to talk about human life in that way but you have to think in terms of movable property. The way large animals are treated legally is very close to slave law,” Holden explained. “They do treat people like runaway horses, or runaway livestock.”

But, as the ads illustrate clearly, the runaways were individuals with distinctive personalities and with families. Now the ads collected in a searchable database might help African American genealogists reconstruct those families that slavery tore apart.

The archive “takes them so far beyond that 1870 wall,” explained Reinette Jones, reference librarian and researcher in UK Special Collections who is co-creator of the Notable Kentucky African-Americans Database.

To reach back into a family’s history, genealogists typically search census records for information about family groups, births, places of residence and the like. But before the 1870 census enslaved African Americans appeared only as property, perhaps with a first name or an age but often simply enumerated with other possessions. They didn’t appear as individual humans with full names and family groups until the first census after emancipation, in 1870.

Jones said this archive opens up additional information that people who want to break through that wall can use. Linking it with other sources, “you can go through and possibly piece together the genealogy.”

Freedom on the Move launched in 2018 with ads that had been collected for other research projects, bringing them into one database. But by last year it was beginning to look for other institutions around the country that could add to the collection.

Jones was the person Holden reached out to as she sought a way to bring Kentucky and UK into the Freedom on the Move project. Soon, they assembled a meeting that included two others from UK Special Collections, Jennifer Bartlett, oral history librarian, and Kopana Terry, curator of the newspaper collection at UK.

They met in August last year and by the fall began planning to bring in students to find the ads. The students began work in mid-March. This summer the team is working with Cornell to sort out any glitches in uploading the Kentucky information into the national database and expects the first Kentucky ads will go online in late July or early August.

It is Jennifer Bartlett who sorted out how to make the technical aspects of the project work. “We wanted to make it as easy as possible (for the students) to go in and concentrate on the papers themselves,” she said. In early newspapers the ads can be hard to find because they might just be words in type without images or anything else to separate them from other items on the pages. Sometimes, too, Jones said, the ad may start off being about a missing horse and it’s only farther down that you see a human ran away with the horse.

Without getting deep into the technical aspects, because the ads are clipped in Photoshop, all the metadata associated with the ad — publication, date, page, column and how many slave ads are on the page — is automatically recorded along with a rough, searchable transcription. That means the ads can much more easily be searched for information that could add to the understanding of slavery in the United States — whether it’s by occupation (seamstress, groom, blacksmith, carpenter, etc.) or by former owners, or physical characteristics like scars or missing digits. The system is also designed to allow researchers to click through and see the entire page where an ad appears, providing context for that moment in time.

Using this system — which Bartlett hopes to be able to hand over to other institutions as they join the Freedom on the Move project —- the students had clipped over 700 ads by the end of the semester, barely nine months after the team first started planning. “This team worked together better than any team I’ve ever been on,” Jones said.

All of this means that when the effort started there were both newspapers to search and the technical know-how to make the findings available to the world. For Kopana Terry that means anyone going forward will be able to see the humans in the story that was slavery in the United States. She believes a vast collection of thousands upon thousands of runaway slave ads will have “far more impact” than reading one or two. “Imagine how humanizing it’s going to be to look at all those ads in a single database and realize that those are people, those are people,” she said. “You really get an insight into who these people were.”

The ads open a window on the people trying to break free, Holden agrees, but they also tell a story about the slaveholders and the society that tolerated, profited from slavery. “Enslavers knew how much enslaved people didn’t want to be slaves and that is pervasive. Resistance was pervasive, it was everywhere, all the time, and it was right there in the newspaper next to ads for corn and candles.”

Beyond the researchers who will learn more about slavery in this country, the team believes Freedom on the Move represents a tremendous resource for younger people. “It’s important for many of the students, especially in K through 12, to learn about slavery through resistance,” Holden said.

Jones welcomed the idea that in the current political environment using runaway slave ads as a teaching tool might meet with pushback.

“Let them push. This is part of the resistance,” she said. “Come on and push, help promote this project. I dare you to push.”