Youth suicide rates are higher where services are scarce

Published 6:06 am Thursday, December 1, 2022

MELISSA PATRICK

Kentucky Health News

Counties that have shortages of mental-health providers tend to have seen their rates of youth suicide increase in recent years, a study has found.

The study, published in JAMA Pediatrics, found that after adjusting for demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, counties with a mental-health workforce shortage were associated with an increased youth suicide rate, and an increased youth firearm suicide rate, when compared to counties with no or partial mental health shortage designations.

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among U.S. adolescents, with rates rising over the last decade. This is also true in Kentucky. Every county in Kentucky is officially designated as a Mental Health Professional Shortage Area, except Boone, Campbell and Grant counties in Northern Kentucky.

“Our results underscore the critical need to expand the mental health professional workforce in counties across the country,” lead author Dr. Jennifer Hoffmann, an emergency medicine physician at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, said in a news release. “In addition, policies that restrict firearm access to young people may be considered as a suicide-prevention strategy.

Using youth suicide data from every U.S. county, the researchers found there were 5,034 suicides by youth between the ages of 5 and 19 from 2015 to 2016, with an annual suicide rate of 3.99 per 100,000 youth in that age group. The study found that among all the counties where a youth suicide occurred, more than two-thirds, or 67.6%, were designated as mental-health workforce-shortage areas.

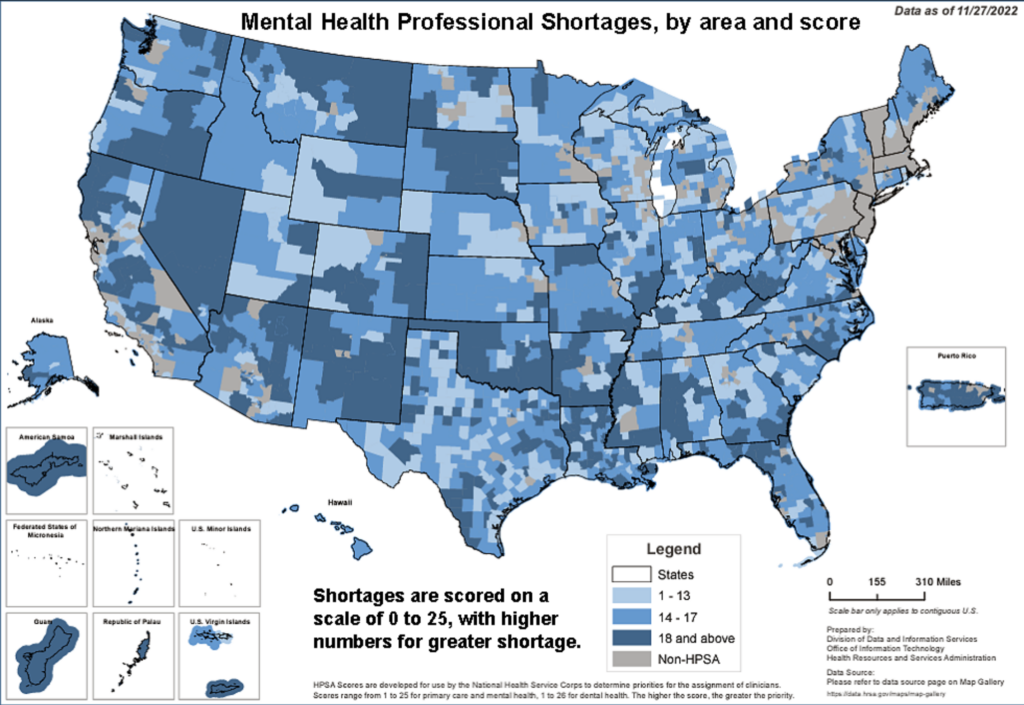

The designation is made by the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration, which assigns a score between 0 and 25, with higher scores indicating greater shortages. The study found that the adjusted youth-suicide rate increased 4% for every 1-point increase in the score.

It also found that there were geographic disparities, with higher suicide rates in rural and high-poverty areas, where mental-health professionals are scarce.

“Counties with mental-health HPSA designation had more uninsured children, lower educational attainment, higher unemployment, higher poverty, higher percentages of non-Hispanic White residents, and were more often rural, compared with counties with partial/no HPSA designation,” the researchers write.

Hoffmann offered several ways to improve access to mental-health care for youth.

“Mental-health workforce capacity can be increased through integration of mental-health care into primary-care settings and schools, and through expansion of telehealth services,” Hoffmann said in a news release. “Improving reimbursement rates for mental-health services may further aid in recruitment and retention of mental health professionals, and hopefully reduce suicide rates among young people.”

Dr. Aaron Carroll of the Indiana University School of Medicine and Denise Hayes of the university’s School of Public Health, argued in an accompanying editorial that money directed at hiring more mental-health care professionals alone will not solve this problem.

“Even if the money was available, it would be nearly impossible to fix this problem through hiring alone,” they write. “We have never valued mental health the way we do physical health. Of the more than $3 trillion we spend on health care each year, a pitiful amount is dedicated to behavior and psychiatric issues.”

The release says mental-health problems are among the most common precipitating factors for youth suicide. Further, it says that up to one in five children in the U.S. has a mental health condition, but only about half of children who need mental health care receive it.

“Countless youth need help,” Carroll and Hayes write. “Unfortunately, help is often in short supply.”

According to the 2021 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 19% of Kentucky’s high school students seriously considered attempting suicide during the 12 months before the survey and 15% of them made a plan about how they would do it in that same time frame. And 9.5% of them said they had actually attempted suicide one or more times in the year prior to the survey.

Further, firearm deaths among Kentucky children between the ages of 1 and 19 increased 83% between 2013-15 and 2018-20, from 3.6 to 6.6 deaths per 100,000, according to data published in the 2022 Kids Count County Data Book.

Dr. Lindsay Ragsdale, chief medical officer for Kentucky Children’s Hospital, recently told Kelsey Souto of WKYT-TV that the hospital is seeing an influx of youth coming into the emergency department experiencing mental-health crises, due to gaps in outpatient resources.

“I think we have to start talking to children in adolescence about what they’re going through,” said Ragsdale. “To make it okay to say ‘I’m not okay.’”

Kentucky’s youth are asking for more mental health resources, according to a Kentucky Youth Advocates survey that asked them what state leaders should prioritize. Some of their responses were included in the County Data Book.

“Mental health should be a big priority. As someone that has anxiety and it affects me everyday not just mentally but also physically, it is the best feeling knowing that people really care about me and the way I feel,” said a 14-year-old named Elizabeth from Daviess County.

Help is available for anyone who is thinking about suicide or knows someone who is considering it. To get help, dial 988, which is the new suicide and crisis lifeline. The three-digit mental health crisis hotline offers free, confidential support and is available 24 hours a day.