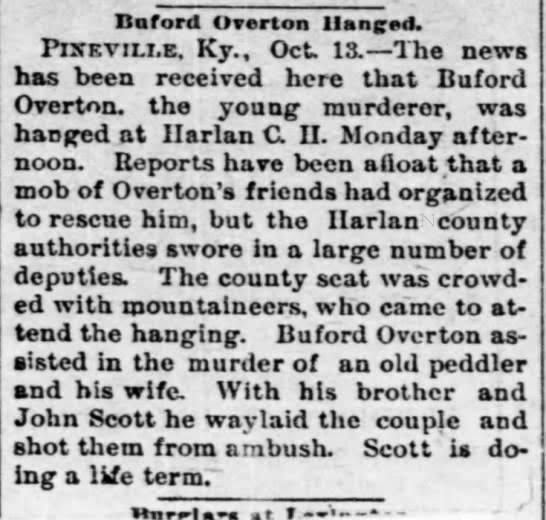

Jadon Gibson: A Murder in Harlan – finale

Published 8:35 am Friday, October 7, 2022

JADON GIBSON

Contributing columnist

In years past, it was common for songs to be written and sung about happenings like the murders of Gus and Julia Loeb. Songs about deaths of presidents, train wrecks, robberies, duels and many other events were common themes. Information about such events were often passed in this manner.

The Peddler and His Wife was the song about the Loebs, recorded by Alan Lomax in 1937 with Blind James Howard doing the vocals. It was quite popular in its time.

When Sheriff Grant Smith and his deputies arrived at the newly completed gallows, Buford Overton was sitting in the back of the wagon. The crowd noise increased as it was to be the first legal hanging in “Bloody Harlan” since the Civil War. Several began singing the song about Gus and Julia Loeb, and a few others joined in.

The Peddler and his wife

“Just as the sun was rising high on a day in merry June The birds were singing in the trees. All nature seemed in tune.

A peddler and his wife were traveling on the lone highway Sharing each other’s toils and cares. They both were old and gray.

They were laboring hard… A living was to be made They did not think That men their lives would take.

But alas a scheme was laid by Cain and some treacherous men whose hearts were hard as any stone and did not care for sin.

Hiding by the side of the road with hearts like murderer Cain With voices hushed and weapons aimed To kill the weary twain.

Just then a wagon came in view. Shots rang out on the air Poor one fell out upon the ground and tossed her dying head.

The men rushed up and took her gold. Poor lady she was dead.

The horse rushed on with the dying man ‘til friends checked its speed But alas, alas, it was too late to stop that horrible deed.

How can those men expect to live who did this terrible crime So now the old couple is sleeping in their tomb Their souls gone above Where thieves cannot disturb them where all is peace and love.”

There had been hangings in many other locations and area mountaineers had heard and learned songs that had been written about them. Some traveled to other locations to witness a hanging. That’s why as many as 3,000 or more came to Bloody Harlan to see Buford pay for his horrible deed. Many brought their whole family and food to eat.

After a humble prayer by Rev. Browning of Harlan, the sheriff proceeded to read a directive from Judge W. F. Hall that “Buford Overton was to be hanged on October 18, 1896.”

“Buford, do you have anything to get off your chest?” Sheriff Smith asked the doomed man. “There’s a whole of people here that would like to hear what you have to say.”

“I am sorry for what happened,” he said with his head hung low and his voice so low that very few heard what he said.

Not many in the crowd believed him. They thought he was sorry that he got caught.

“Trouble always seemed to follow me,” he continued. “I’ve been treated bad all my life. I was an orphan. I don’t think I’ve ever had anyone who cared about me, so I didn’t care about them either.

“My mistake was getting in with the wrong crowd. I see boys and girls here who seem to be about the same age I was when I started to go wrong. You’ll do better if you don’t get mixed up in the devil’s work. Don’t take up guns, whiskey and gambling like I did. It can really get you in trouble.

“Friends or people you trust or look up to sometimes try to get you to do a little thing but then something bigger and bigger. That’s what happened to me.

You see what it got me. In just a few minutes I’ll be hanging here by my neck.

“They say if your neck isn’t broke by the fall it is painful to hang there by your neck. Actually I mean my neck, kicking until I’m finally dead. I hope it breaks my neck.

“I want you to do what is best for you. The best thing you can do is stay in school and start thinking about your future… think about being a doctor, owning and running a business, working on a train or something. If you can picture yourself doing it… you can do it.”

John Ward yelled out asking: “Buford, did you kill Gus and Julia Loeb?”

“I won’t say if I did or not,” he answered. “But I will say I’m not the one responsible.”

When he was asked additional questions about the murder he became despondent, his eyes tearful.

Sheriff Smith tied his hands while one of the deputies tied his feet. The prisoner asked if Jane Tipton would come up and talk to him briefly. He told her goodbye. Dr. Nolan checked his heart rate again and it was 96 beats per minute.

The crowd became very quiet after joining together in a song. The rope was put around Buford’s neck and a black hood over his face.

“John Scott and my brother were there with me,” he blurted quickly and sternly from beneath the hood, knowing he would not have another opportunity. “We were all there when the Loebs were killed.”

Buford could be heard quietly praying after which the sheriff chopped the rope releasing the trapdoor. Buford’s body dropped through before jerking to a stop with a whomp. It spun several times to the right and then several times to the left, alternating less and less until it became still. His neck was broken. After a while Dr. Nolan checked his pulse and it was nonexistent. Buford was dead.

The spinning of the body was due to a common practice at hangings. The rope would be twisted before being put around the victim’s neck and it caused the body to spin in one direction and then the other. This continued for several rotations before the spinning stopped. His neck was broken. In hanging it meant he felt only a brief pain.

After a half hour, Buford’s body was cut down and taken up Clover Fork where he was buried. None of Overton’s family members were present.

Buford spoke of John Scott and his brother William “Billy” Overton just before he was hanged. Jon Scott was tried and sentenced to prison for life at hard labor. Former Sheriff Enos “Bear” Hensley shot and killed Billy Overton but further information about the killing has not been found.

Jadon Gibson is a freelance writer from Harrogate, Tennessee. His stories are both historic and nostalgic in nature. Thanks to Lincoln Memorial University, Alice Lloyd College and the Museum of Appalachia for their assistance.